Country Carers by Margaret Pittaway

Rural Women New Zealand (RWNZ) has over 90 years of history providing care for people living in rural communities. The Bush Nurse Scheme evolved from the need to provide assistance in the home to women who were struggling to continue with the daily needs of busy farming households and family.

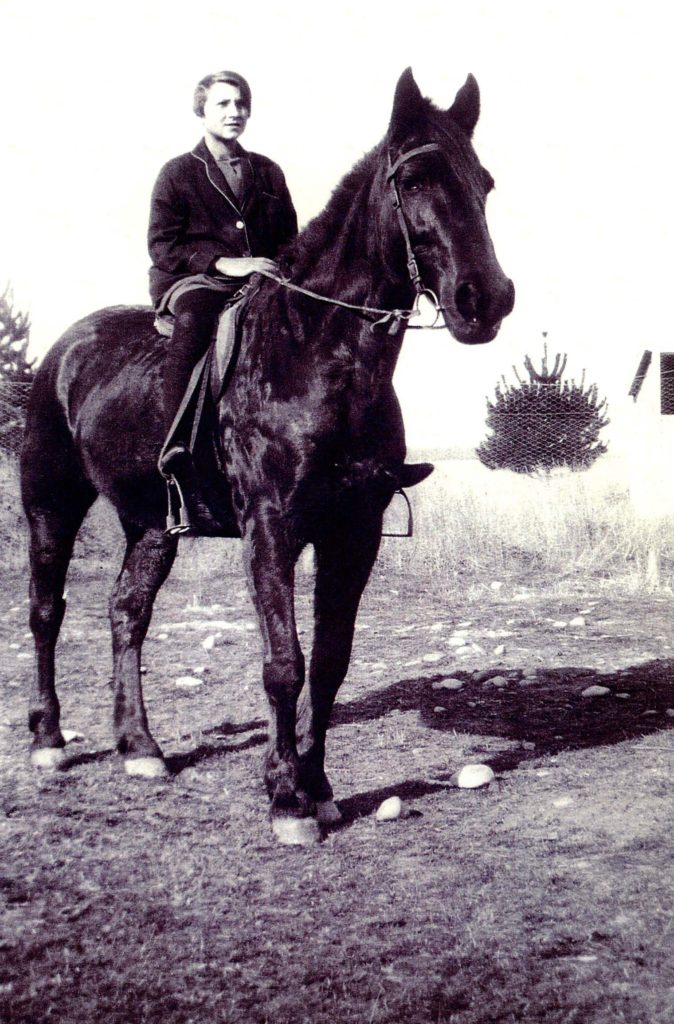

Bush nurses went out on horseback to remote areas to provide postnatal care and to ensure that new mothers and babies were thriving. Respite homes were provided to enable women desperately in need of a break from the daily household demands, and housekeepers were provided to keep the family in good care.

Today RWNZ continues to pay for short-term emergency care to assist and support rural families when they are experiencing difficulties.

For anyone, living in our own home with family around us when recovering from an illness or needing long term care is desirable, as it provides the best environment for happiness, wellbeing and recovery.

The downside for carers living and working in rural areas is that there are many obstacles, whether the carer is in paid employment, or is caring for a family member at home. Distance and isolation are the obvious barriers for all rural carers. The inconvenience of being removed from central locations means that time and travel costs add to the problems with no hope of full recompense. This applies to carers who use their own car for work purposes, as well as to family members who act as carers and have the need to transport a family member to specialist services.

Working in isolation means that there is no peer support, which is so valuable to discuss day-to-day problems of management and to share the problems encountered, or just to have a coffee and a laugh. It is often difficult to find suitably qualified staff to allow for holidays and sickness leave, and retaining the services of staff can also be challenging.

Community-based carers experience problems with continuing education to ensure that their skills and competencies are up-to-date, although online training does fulfil some of these requirements, provided that reliable broadband coverage is available.

Communication can be challenging, and the use of mobile phones and iPads, commonly used in urban areas, are not as reliable in rural areas where there is poor or no coverage. On occasion, there may be safety issues for carers travelling in isolated areas in poor weather and road conditions.

Accessing equipment and supplies in rural areas can also cause problems and frustrations, particularly when new improved treatment methods become available, and are only accessible to those who live and work in centralised areas.

While there may be many problems for carers, it is also an employment opportunity for those who choose to live in rural areas where the friendships, support and lifestyle often more than compensate for the challenges.

Margaret Pittaway

Rural Women New Zealand Health and Social Development Spokesperson