A Never Ending Love Story

When Isobel Reed married Alfred Hamish Reed in 1899, she inserted the word ‘cherish’ into her vows in place of the traditional obey. It was a vow she was always to keep. By Katherine Findlay

For her husband, ‘until death do us part’ was more of a problem. He believed their love was eternal, and when his beloved ‘Bello’ or ‘Belle’ died in 1939, he was to live for another 36 years, still considering himself to be a married man, confident that they would be reunited in the hereafter.

“I am persuaded that the exit of my beloved from this life opened the door to a richer, more abundant life, where personality, love, and opportunity for service must still endure, where she awaits our glad reunion, and from whence I believe she is still permitted to touch this life of mine,” he wrote in Isobel Reed, Her Book, a personal tribute he completed not long after her death.

Theirs is a story of love, faith and caring.

Belle was “the only girl I ever cared two straws about” he confessed to her in an early letter. She apparently turned down two other suitors in favour of the young (he was nine years her junior) ex-gumdigger from the north. They met when A.H. (as he came to be known) and his brother boarded with Isobel’s parents, who ran a confectionery shop in Auckland’s Karangahape Road. Once she’d established that ‘Mr Alf,’ as she quaintly addressed him in one of their many letters, was a staunch Christian gentleman, the attraction between them flourished.

Soon after their engagement they were temporarily separated. A.H. got a job in Dunedin managing The Typewriting Company. They corresponded in shorthand, developing their own special symbol for a kiss on the back of an envelope. He expressed concern for her health, and she reminded him of the need for a good thick winter suit and flannels.

After their marriage Isobel and her husband established a new business in Dunedin. He’d begun to sell and later publish religious texts. Both became Sunday school teachers, and their strong faith saw them through the heartbreak of Belle’s miscarriage late in her only known pregnancy.

A.H’s nephew Clif was like a son to them. Based in Wellington, while A.H. always lived in Dunedin, Clif (christened Alexander Wyclif) became his uncle’s partner in New Zealand’s most successful 20th century publishing firm, A.H. & A.W. Reed. A.H wrote the first of his many books especially for Isobel. It was a small handwritten, hand-crafted volume which he bound himself – a labour of love never intended for wide distribution.

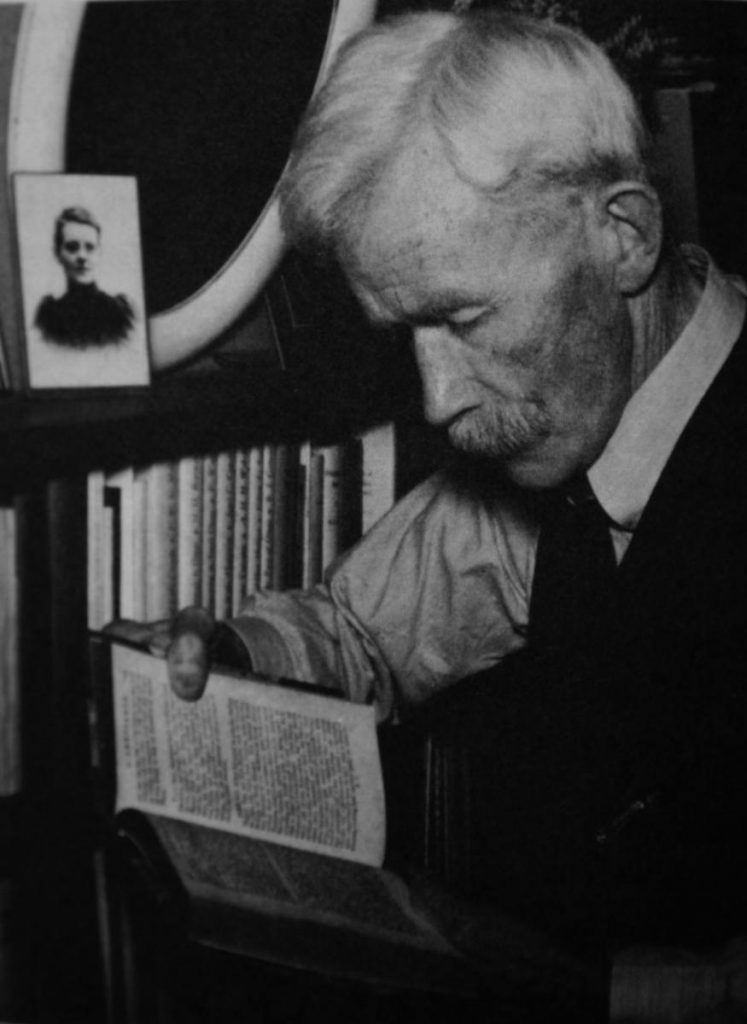

Begun in 1916 when he was awaiting overseas deployment, he called it In and Around Featherston Military Camp and (Mostly) Elsewhere. He was 40 and, because of his clerical skills (particularly shorthand) and his age, the call to arms never came. At that time he and Belle had been married for 17 years. Their closeness is evident on every page. It is clear that he is always thinking of her as he writes. The word YOU is quaintly capitalised. He wonders what she might think about holidaying in a wonderful place he’s discovered on his walk. Her photograph takes pride of place in his Spartan military hut.

The Mostly Elsewhere records a walking trip he took in the Whanganui River area and the lower slopes of Mt Ruapehu, sleeping under the stars and eating at boarding houses along the way. It’s a precursor to the marathon walks and books about them he was to become famous for later in the century. This charming book was re-issued in a facsimile edition and retitled First Walks in New Zealand to mark the centenary of the House of Reed.

The original clothbound volume was presented to Ray Richards by Clif Reed as a retirement gift in 1976. Now in his 80s, Ray spent many years working for the Reeds before setting up his own literary agency, which he still owns. His association with the Reeds goes back to his Dunedin childhood. Ray’s father was the minister of the Mornington Methodist church, where A.H. Reed was the Sunday School Superintendent. A.H. was Ray’s father’s walking companion on the Dunedin hills.

“I was about eight years old,” Ray recalls. “They were Mr and Mrs Reed to me.” He recalls Isobel as a sweet and gentle woman and describes the couple as ‘heart companions’.

“There was nobody else in Dunedin who was family, and if they needed to be thrust together, that thrust them together. They lived unto each other and unto their Christian faith, and for the business”.

In January 1938, as they were about to go on holiday, Isobel Reed suffered a heart attack. The doctor prescribed absolute rest. To make the best of things A.H. turned their bedroom into a sitting room and they had their holiday at home. When necessary he carried Belle up and down the stairs. Six months later A.H. came home to discover Belle in great pain.

“Alfo, perhaps I’m going to leave you, and if so, I love you,” she said to him. He kept an all-night vigil, and the following morning she was taken to hospital. Over the weeks A.H. walked from his office to the hospital several times a day to visit her.

When she was well enough to return home, A.H. carried Belle from her hospital bed to a taxi, and then to their upstairs bed. When the stairs became too much for both of them he relocated the bedroom downstairs.

A former Sunday school pupil came in to care for Isobel in the mornings while A.H. went to his office. In the afternoons he came home. Sometimes they’d sit on the porch and he’d read to her. In bed each night, he’d sing a favourite hymn.

January 22, 1939 began as usual, with A.H. bringing Isobel breakfast in bed. He helped her to dress. They listened to a church service on the radio, then friends visited.

After tea Bell felt unwell and went back to bed. She asked her husband to put his arm around her and read to her. Shortly thereafter she died.

A.H. lived on, building a cottage on land adjoining the larger house he’d so agreeable shared with his Belle. He dedicated himself to philanthropy, writing, and his astounding series of walks throughout New Zealand.

In his late 90s his hearing deteriorated, and A.H. became somewhat forgetful, but apart from a couple of short hospital stays he was able to live independently. In 1974 A.H. Reed was knighted for services to literature and culture and died the following year, aged 99.

It had been such a long wait that one likes to think that somewhere, someplace, glad reunion did indeed take place.

You can purchase some of A.H. Reed’s books on TradeMe.

© Family Care NZ

Photo: Ray Richards/A.H. & A.W. Reed Estate